WASHINGTON - How will the public react if the federal government shuts down next week?

Public polling around the two partial shutdowns between November 1995 and January 1996 provides a sense of what to expect, although reactions then may have been unique to that era's circumstances and outsized personalities.

The first partial shutdown occurred on November 14, 1995, after President Clinton and Republican leaders failed to reach an agreement to keep the government running. More than 800,000 "non-essential" federal workers were furloughed.

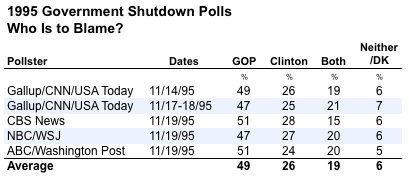

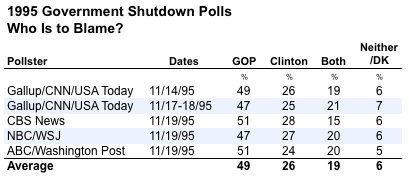

That night, Gallup conducted a national survey for CNN and USA Today that showed nearly twice as many Americans blaming Republican leaders in Congress for the shutdown (49 percent) rather than Clinton (26 percent) or both equally (19 percent).

Gallup also found a 49 percent to 36 percent plurality said they preferred Democrats to Republicans in "dealing with the tough choices involved both in cutting programs to reduce the budget deficit and still maintaining needed federal programs." That result was a significant change from Gallup's finding four months earlier, showing the two parties at near parity on the same question -- 44 percent preferred the Republicans and 43 percent preferred the Democrats.

Two days after the shutdown began, Republican Speaker Newt Gingrich met with reporters and appeared to blame the breakdown in talks that led to the shutdown as the result of his being snubbed by Clinton on a return flight from Israel the previous week. As the Washington Postreported on November 17, 1995:

The remarks produced a firestorm of protest from Democrats, including a White House release of aphoto showing Clinton and Gingrich talking during the flight. The impression was amplified by a New York Daily News front page (via Wikipedia):

Over the next few days, national polls conducted by four media organizations generally confirmed Gallup's initial findings. Despite slightly varied question wording, all four found essentially the same thing: By nearly two-to-one margins, Americans blamed the Republican leaders more often than President Clinton for the partial government shutdown.

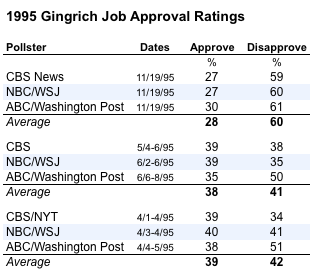

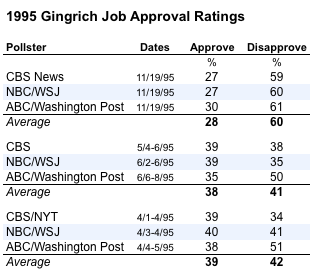

Not surprisingly, the surveys also showed a big jump in Speaker Gingrich's disapproval rating. Polls conducted at the end of that week by CBS News, NBC/Wall Street Journal and ABC/Washington Post gave Gingrich an average rating of 28 percent approve, 60 percent disapprove. The disapprove numbers had jumped roughly 20 percentage points from previous measurements by the same three polls earlier that year.

These numbers left the most lasting impressions of public opinion at the time, but they present challenges to those of us trying glean lessons for the current budget impasse.

First, Newt Gingrich played an obviously unique role in shaping reactions to the 1995 shutdown, because of both his notorious "cry baby" remarks and his previously established image. As the table above shows, he received net negative ratings well before the crisis. Five months before the shutdown, in June of 1995, a CNN/USA Today/Gallup found 54 percent of Americans considered Gingrich's views "too extreme," while 33 percent said he was "generally in the mainstream."

By comparison, current Republican Speaker John Boehner's profile is lower and less negative. In January, just a few weeks after assuming office, the ABC/Washington Post poll gave him a net positive job approval rating (39 percent positive, 27 percent negative). Boehner has also received net favorable ratings from other pollsters (USA Today/Gallup, CNN/ORC, Bloomberg) whose questions explicitly identified him as the House Speaker.

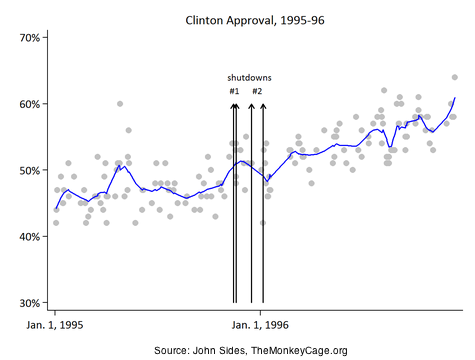

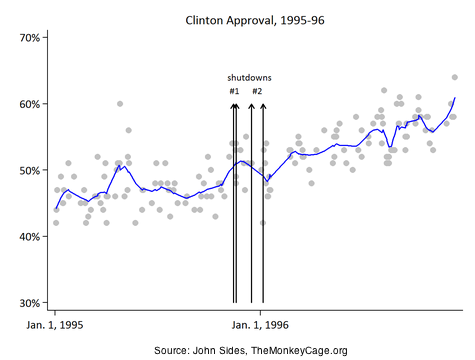

Second, while the shutdown helped increase negative perceptions of Gingrich and the Republicans, the impact on Clinton's image was less clear. Political scientist John Sides plotted all of Clinton's approval ratings over the course of 1995 and 1996 and found it "largely unaffected by the first shutdown," in part because the President's ratings were already on the rise in October 1995.

Sides opts against making much of the small decline in approval following the second partial shutdown that occurred in December 1995 and continued through early January 1996. He asserts that many things, including random noise in the chart, might explain the momentary variation in Clinton's approval ratings.

That said, other findings at the time are consistent with the notion of a small, temporary decline in Clinton's approval rating. Another CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll in mid-December 1995, for example, asked Americans if the shutdown had changed their impressions of both President Clinton and the Republicans in Congress. Not surprisingly, a large majority (62 percent) said their impressions of Republicans had worsened (23 percent were more positive), but nearly half (49 percent) also said their impression of Clinton had grown more negative as result of the government shutdown (35 percent said they had become more positive).

Third and finally, for obvious reasons, many of the more specific questions did not allow for consistent measurements to track attitudes before, during and after the shutdown. One poll from 1995 that asked Americans who they might hold responsible for a government shutdown before it happened was readily available: ABC News and The Washington Post found that as of mid-October 1995, a plurality were already primed to blame the Republicans rather than Clinton for a shutdown (49 percent to 27 percent).

A handful of measures, however, did indicate erosion of the Republican position.

For example, CBS News tracked a question asking Americans whether they trusted Clinton or the Republicans more "to make decisions about balancing the federal budget." Before the shutdown, in July 1995, Republicans held a five-point advantage (44 percent to 39 percent). It disappeared immediately after the first shutdown, as 41 percent trusted each party. By January 1996, Democrats had a small advantage (44 percent to 41 percent) which narrowed only slightly in February (41 percent to 39 percent).

Republican pollster Glen Bolger found a similar pattern on measurements on the "generic" that asks voters if they intend to support a Democratic or a Republican candidate for the U.S. House: "[A] one point deficit in October (41% GOP/42% Dem) shifted to a three point deficit in December (41% GOP/44% Dem) and then dropped to eight points in January (38% GOP/46% Dem)."

So what does all of this tell us about how the public may react to another government shutdown in the near future?

Perhaps not much, given the strong and unique role played by Speaker Gingrich in 1995. But history does have at least two important implications:

First, Americans were unhappy about the 1995/1996 shutdowns, and their reaction did create some blowback for the Republicans. A present day shutdown will likely have negative consequences for at least some of our national leadership.

Second, pollsters asking Americans about their expectations of who might be responsible for a future shutdown resemble reactions from 1995. An ABC/Washington Post poll conducted earlier this month finds more Americans holding Republicans responsible (45 percent) than President Obama (31 percent) for the fact that "the federal government might have to partially shut down later this month." Similarly, a Quinnipiac University poll from February finds a similar result: 47 percent would blame the Republicans and 38 percent President Obama "if the federal government shuts down." However, a Pew Research/Washington Post survey in February found Americans more divided, with 36 percent ready to blame Republicans and 35 percent ready to blame Obama.

Will these expectations predict actual reactions, as they did in 1995? If the negotiations remain at an impasse, we will soon find out.

Public polling around the two partial shutdowns between November 1995 and January 1996 provides a sense of what to expect, although reactions then may have been unique to that era's circumstances and outsized personalities.

The first partial shutdown occurred on November 14, 1995, after President Clinton and Republican leaders failed to reach an agreement to keep the government running. More than 800,000 "non-essential" federal workers were furloughed.

That night, Gallup conducted a national survey for CNN and USA Today that showed nearly twice as many Americans blaming Republican leaders in Congress for the shutdown (49 percent) rather than Clinton (26 percent) or both equally (19 percent).

Gallup also found a 49 percent to 36 percent plurality said they preferred Democrats to Republicans in "dealing with the tough choices involved both in cutting programs to reduce the budget deficit and still maintaining needed federal programs." That result was a significant change from Gallup's finding four months earlier, showing the two parties at near parity on the same question -- 44 percent preferred the Republicans and 43 percent preferred the Democrats.

Two days after the shutdown began, Republican Speaker Newt Gingrich met with reporters and appeared to blame the breakdown in talks that led to the shutdown as the result of his being snubbed by Clinton on a return flight from Israel the previous week. As the Washington Postreported on November 17, 1995:

"This is petty," [Gingrich] told reporters. "[But] you land at Andrews [Air Force Base] and you've been on the plane for 25 hours and nobody has talked to you and they ask you to get off the plane by the back ramp… . You just wonder, where is their sense of manners? Where is their sense of courtesy?"

The remarks produced a firestorm of protest from Democrats, including a White House release of aphoto showing Clinton and Gingrich talking during the flight. The impression was amplified by a New York Daily News front page (via Wikipedia):

Over the next few days, national polls conducted by four media organizations generally confirmed Gallup's initial findings. Despite slightly varied question wording, all four found essentially the same thing: By nearly two-to-one margins, Americans blamed the Republican leaders more often than President Clinton for the partial government shutdown.

Not surprisingly, the surveys also showed a big jump in Speaker Gingrich's disapproval rating. Polls conducted at the end of that week by CBS News, NBC/Wall Street Journal and ABC/Washington Post gave Gingrich an average rating of 28 percent approve, 60 percent disapprove. The disapprove numbers had jumped roughly 20 percentage points from previous measurements by the same three polls earlier that year.

These numbers left the most lasting impressions of public opinion at the time, but they present challenges to those of us trying glean lessons for the current budget impasse.

First, Newt Gingrich played an obviously unique role in shaping reactions to the 1995 shutdown, because of both his notorious "cry baby" remarks and his previously established image. As the table above shows, he received net negative ratings well before the crisis. Five months before the shutdown, in June of 1995, a CNN/USA Today/Gallup found 54 percent of Americans considered Gingrich's views "too extreme," while 33 percent said he was "generally in the mainstream."

By comparison, current Republican Speaker John Boehner's profile is lower and less negative. In January, just a few weeks after assuming office, the ABC/Washington Post poll gave him a net positive job approval rating (39 percent positive, 27 percent negative). Boehner has also received net favorable ratings from other pollsters (USA Today/Gallup, CNN/ORC, Bloomberg) whose questions explicitly identified him as the House Speaker.

Second, while the shutdown helped increase negative perceptions of Gingrich and the Republicans, the impact on Clinton's image was less clear. Political scientist John Sides plotted all of Clinton's approval ratings over the course of 1995 and 1996 and found it "largely unaffected by the first shutdown," in part because the President's ratings were already on the rise in October 1995.

Sides opts against making much of the small decline in approval following the second partial shutdown that occurred in December 1995 and continued through early January 1996. He asserts that many things, including random noise in the chart, might explain the momentary variation in Clinton's approval ratings.

That said, other findings at the time are consistent with the notion of a small, temporary decline in Clinton's approval rating. Another CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll in mid-December 1995, for example, asked Americans if the shutdown had changed their impressions of both President Clinton and the Republicans in Congress. Not surprisingly, a large majority (62 percent) said their impressions of Republicans had worsened (23 percent were more positive), but nearly half (49 percent) also said their impression of Clinton had grown more negative as result of the government shutdown (35 percent said they had become more positive).

Third and finally, for obvious reasons, many of the more specific questions did not allow for consistent measurements to track attitudes before, during and after the shutdown. One poll from 1995 that asked Americans who they might hold responsible for a government shutdown before it happened was readily available: ABC News and The Washington Post found that as of mid-October 1995, a plurality were already primed to blame the Republicans rather than Clinton for a shutdown (49 percent to 27 percent).

A handful of measures, however, did indicate erosion of the Republican position.

For example, CBS News tracked a question asking Americans whether they trusted Clinton or the Republicans more "to make decisions about balancing the federal budget." Before the shutdown, in July 1995, Republicans held a five-point advantage (44 percent to 39 percent). It disappeared immediately after the first shutdown, as 41 percent trusted each party. By January 1996, Democrats had a small advantage (44 percent to 41 percent) which narrowed only slightly in February (41 percent to 39 percent).

Republican pollster Glen Bolger found a similar pattern on measurements on the "generic" that asks voters if they intend to support a Democratic or a Republican candidate for the U.S. House: "[A] one point deficit in October (41% GOP/42% Dem) shifted to a three point deficit in December (41% GOP/44% Dem) and then dropped to eight points in January (38% GOP/46% Dem)."

So what does all of this tell us about how the public may react to another government shutdown in the near future?

Perhaps not much, given the strong and unique role played by Speaker Gingrich in 1995. But history does have at least two important implications:

First, Americans were unhappy about the 1995/1996 shutdowns, and their reaction did create some blowback for the Republicans. A present day shutdown will likely have negative consequences for at least some of our national leadership.

Second, pollsters asking Americans about their expectations of who might be responsible for a future shutdown resemble reactions from 1995. An ABC/Washington Post poll conducted earlier this month finds more Americans holding Republicans responsible (45 percent) than President Obama (31 percent) for the fact that "the federal government might have to partially shut down later this month." Similarly, a Quinnipiac University poll from February finds a similar result: 47 percent would blame the Republicans and 38 percent President Obama "if the federal government shuts down." However, a Pew Research/Washington Post survey in February found Americans more divided, with 36 percent ready to blame Republicans and 35 percent ready to blame Obama.

Will these expectations predict actual reactions, as they did in 1995? If the negotiations remain at an impasse, we will soon find out.

No comments:

Post a Comment