After a lobbying and campaign finance blitz totaling millions of dollars over the past year, the industry appeared to be on the verge of getting a special provision in the budget bill that would block increased government oversight of their schools. The matter was still not decided, they insisted.

“We need you to make calls this weekend!” urged the letter from the group to its more than 1,600 member colleges. “Members and staff are meeting over the weekend to finalize the details of the [bill]. We encourage you TODAY and throughout this weekend to contact the offices of your Congressman/Senators urging them to support inclusion of the … amendment in the final package.”

The email communique was a last-ditch bid to protect the massive federal subsidies that have fueled the spectacular growth of what is now a multibillion-dollar, publicly traded industry in higher education. With student loan defaults growing alongside profits at many of the largest companies, the government is seeking more accountability for colleges that promise training for careers, but leave students with unsustainable debts.

As the stakes for this fast-growing industry rise, so have the dollars spent on an expansive lobbying campaign to ensure the government money keeps flowing.

Some of the largest publicly traded college corporations receive nearly 90 percent of their revenues from federal student aid programs. While government money fuels increased enrollments and record profits, the industry has poured increasing amounts of those proceeds into an unprecedented effort to preempt the rules through greater influence in Washington.

In other words, an industry that derives a vast majority of its revenue from federal funding is actively using that money to fight government efforts for accountability.

The last-minute scramble earlier this month was only the latest chapter in the industry’s yearlong battle against increased federal oversight of their schools.

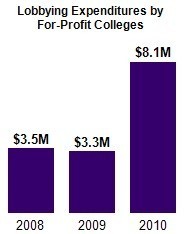

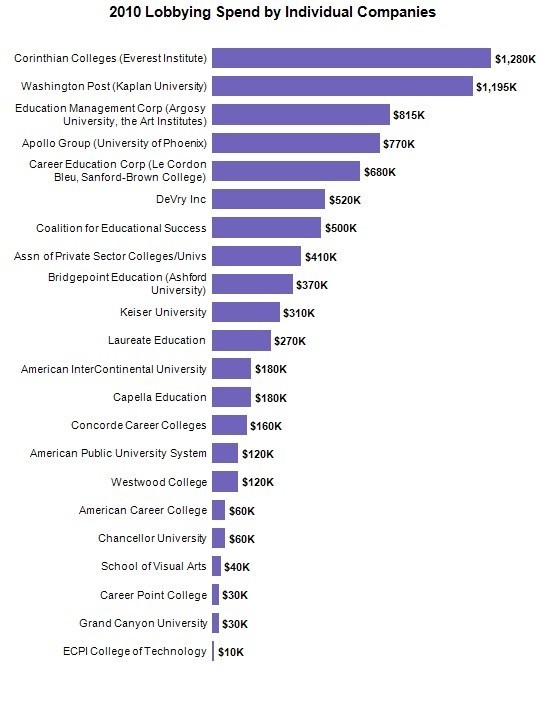

Overall, the industry spent more than $8.1 million on lobbying in 2010, up from $3.3 million in 2009, according to a Huffington Post analysis of lobbying data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics.

(Source: Analysis of data from the Center for Responsive Politics)

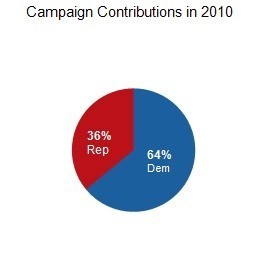

In addition, campaign spending from the industry’s political action committees and executives increased to more than $2 million from $1.1 million between the 2008 and 2010 election cycles, according to a Huffington Post analysis of campaign finance records from the Sunlight Foundation’s website, TransparencyData. The industry’s political action committees and executives spent nearly twice as much on Democrats as on Republicans.

Industry representatives say the uptick in spending for a business that derives most of its money from the government is not at all unusual in Washington.

“It’s not unique in any sense,” said Harris Miller, the president and chief executive of the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities, “any more than it is for traditional higher education lobbying to get earmarks for their schools, or Boeing or defense contractors using their money to promote an agenda, which is to win a contract of the U.S. government.”

For-profit college companies and trade associations have hired a dream team of Washington insiders to lobby on their behalf, however, bringing on 14 former members of Congress, including former Democratic House Leader Dick Gephardt. Some of the most powerful lobby shops in Washington have been employed in the fight: Tony Podesta and the Podesta Group; former Clinton special counsel Lanny J. Davis; numerous former staffers from the Department of Education and the education oversight committees on Capitol Hill.

Until scrutiny of the schools intensified last year, when the Obama administration announced plans for new accountability rules, many of the colleges’ parent companies were known on Wall Street for their exemplary profit margins.

The stakes for industry executives and shareholders have been huge. Andrew Clark, the chief executive at Bridgepoint Education Inc., which owns two online colleges, brought home more than $20 million in compensation last year. Corinthian Colleges Inc., which owns a string of more than 100 campuses across the nation, saw profits increase from $4.5 million in 1999 to more than $146 million in 2010.

Revenues for publicly traded college corporations topped $20 billion last year.

The industry has not been shy about funneling its money into marketing. Ubiquitous advertisements for the colleges fill subway cars in major cities and are plastered on billboards along highways across the country. Advertising Age listed The Apollo Group, which owns the University of Phoenix, as one of the top 100 spenders on U.S. advertising in 2009: The company spent in excess of $377 million, more than Apple Inc.

But the outcomes for students at such schools have prompted deep concerns about the federal government’s increased investments.

Students at for-profit colleges default on federal loans at double the rate of their counterparts at nonprofit schools, according to recently released data from the Department of Education. And although only 10 percent of students nationwide attend such institutions, they account for nearly half of all student loan defaults, leaving the government to pick up the tab.

On average, the tuition at many of the largest for-profit colleges is nearly twice that of in-state tuition at four-year public universities and more than five times the average tuition at community colleges, according to a Senate report released last year.

Critics have pointed to an unfair bargain behind those statistics: Students and taxpayers take on all the risk while the schools reap all the rewards, in the form of profits from federal money.

“Going to college should not be like going to a casino, where the odds are stacked against you and the house always wins,” Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), a vocal critic of for-profit colleges, said at a Senate hearing last fall.

For their part, for-profit colleges argue that they provide educational opportunities for many Americans who would otherwise have no such options, and that additional regulation could deny such students advancement.

“It does literally threaten the existence of hundreds if not thousands of programs, and threaten the ability of hundreds of thousands of students to continue to get an education,” said Miller, of the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities.

Advertisements in Washington newspapers and on websites across the country have broadcast the same message: The Department of Education is trying to prevent students from going to college, especially low-income students who have struggled in other educational fields.

Education advocacy groups, meanwhile, argue the for-profit college rhetoric skillfully twists reality.

“They’ve mastered the art of marketing,” said Jose Cruz, vice president for Higher Education Policy at the Education Trust, a student advocacy organization. “In an attempt to protect the most important revenue source, which are the federal subsidies, they have launched this campaign to appeal to Americans’ belief in choice and opportunity, particularly for those who have been traditionally underserved.”

As the industry pours more money into lobbying, marketing and campaign finance, both Republicans and Democrats in Congress have shown their support.

Its increased clout was on display during a House vote in February, when more than 50 House Democrats, including House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and incoming Democratic National Committee chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.), joined Republicans in voting to block new regulations on the industry.

And during this month’s budget fight, a bipartisan group of House members pushed to prohibit the Department of Education from moving forward with such regulations later this year. The Senate eventually stripped from the budget bill the rider that would have exempted for-profits from further regulation, but the industry has vowed to continue seeking such an exemption.

Many of the lawmakers who voted in support of the exemption in February, and who signed on to a letter urging its inclusion in the budget earlier this month, were the most well-compensated by the for-profit college industry.

“These burdensome and unnecessary regulations unfairly single out the private sector of postsecondary education and will negatively affect the landscape of our nation’s higher education system,” read a letter from six Democratic and six Republican House members urging that the budget compromise include a provision to block additional regulations. Five of the signatories were among the top 10 recipients of campaign cash from the industry, receiving more than $20,000 apiece in the last election cycle.

(Source: Huffington Post analysis of data from the Sunlight Foundation)

AN EXISTENTIAL THREAT

The rules at issue, developed by the Department of Education, are known as “gainful employment” regulations. It’s an effort to measure the quality of for-profit college and nonprofit vocational college programs by analyzing student outcomes in the workplace, gauging whether the schools set students up for careers that will allow them to pay off debts.

Rules requiring that vocational colleges prepare students for “gainful employment in a recognized occupation” have been on the books since the 1970s, adopted following a series of problems with unscrupulous, fly-by-night trade schools that didn’t provide the training they promised. This marks the first time the Department of Education has ever sought to officially define those rules written into the law by Congress.

For-profit colleges say that would pose an existential threat to the industry.

The Department of Education, on the other hand, has said the regulations are designed as both a consumer protection measure for students and a student aid accountability test for the federal government. A final version is expected within months.

The rules have been in the works since 2009, and were first drafted and presented to the public by the Department last summer. According to the draft version, the Department of Education would track students after leaving college and evaluate them using two criteria: whether they are paying down the principal on their student loans and whether graduates have attained an income that allows them to manage debts.

Programs at certain for-profit colleges and other vocational college programs that do not meet targets for student loan repayment or debt levels would be restricted from receiving federal student aid or forced to disclose debt levels to prospective students. As drafted, the rules would allow programs to remain fully eligible for aid even if less than half of students are repaying the interest on loans, plus at least one penny of the principal after graduating or dropping out of the program.

Programs could also remain fully eligible if less than a third of students are repaying the principal on loans, as long as graduates are not spending more than 20 percent of discretionary income toward paying off student loans.

Student advocacy groups say the standards are not overly stringent, since each scenario would allow more than half of students to be behind on repaying the balance of their loans. The industry says there have not been enough studies of the effects the rules would have on the industry.

The rules would not punish entire schools; rather, individual programs that fail to meet the standards could face sanctions. The regulation would not go into effect until the 2012-’13 school year and the rules would punish only the worst 5 percent of offenders during the first year, giving programs time to adjust their curriculum or reduce costs.

“There hasn’t been much discussion about what the regulation actually would do,” said David Hawkins, director of public policy and research at the National Association for College Admission Counseling, whose member colleges include mostly nonprofits. “Instead there has been this hyperbolic, grand debate about limiting student choice. Really what the debate is about is the federal government drawing a line, beyond which they will be prepared to say, ‘I’m sorry, we cannot fund this program anymore.”

The Department of Education estimates the rules would completely restrict federal aid to about 5 percent of for-profit college programs, and that 55 percent of such schools would have to warn students about average debt levels.

Industry estimates, of course, are much higher. A study financed by the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities estimated that 33 percent of students at such schools would be affected.

Rep. Robert Andrews (D-N.J.), an opponent of the regulations who is also one of the top campaign recipients from the industry, said he disagrees with the government’s focus on measuring debts compared to earnings. Instead, he said gainful employment should be measured by job placement that increases a graduate’s income.

“I think the question is how we do this, not if we do it,” Andrews said. “If they don’t place enough students up to a fair standard, kick them out of the program. Whether they’re owned by a for-profit, nonprofit or public institution.”

Davis, the Democratic lobbyist and former special counsel to Bill Clinton, questioned why the the regulations should not be applied to all sectors of higher education.

“If we’re looking at the problem of excessive student debt, it is a problem and there needs to be a national solution,” Davis said. “I, as a liberal Democrat, would say the national solution isn’t cracking down on poor people who default.”

REVOLVING DOOR CULTURE

Many critics of the for-profit sector who have long argued for more oversight say the rules proposed by the Obama administration are simply a reaction to a loose regulatory approach practiced during the administration of George W. Bush.

During those years, the corporations and their regulators developed a distinct revolving-door culture, where administration and congressional officials shifted from policy work for the government to advocacy work for the industry.

Both Bush Education Secretaries, Rod Paige and Margaret Spellings, have worked in connection with for-profit college corporations since leaving their posts. And for the majority of the Bush years, the assistant secretary overseeing higher education in Washington was Sally Stroup, a former lobbyist for the University of Phoenix, the largest of the for-profit college corporations. After leaving the administration in 2006, she became a top aide for the House Education and Labor Committee, now known as Education and Workforce.

That same year, current House Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio), then the chairman of the lower chamber’s education committee, helped to successfully pass legislation that lifted restrictions on federal student aid flowing to online college programs.

The provision nixed a previous rule that required schools to have at least half of students attending ground campus classes in order to be eligible for federal student aid. The old rule’s elimination allowed for unprecedented growth at primarily online, for-profit schools.

DEFINING THE MESSAGE

The final gainful employment rules were supposed to be released last fall, but the Department of Education delayed publishing them after receiving more than 90,000 comments from the public -- the most ever received on any regulation in the Department’s history. Many of the comments came from identical email form letters set up by colleges and trade associations for employees and students to send out -- the byproduct of an extensive online marketing campaign.

Some of the form letters sent in as comments were not even filled out. One filed by Alyssa Hoskins of Edinburgh, Ind., read, “I am a career college student at [INSTITUTION] studying [PROGRAM]. [INSTITUTION] is providing me with the education and training necessary to obtain the job I’ve always wanted as a [CAREER].”

One anonymous comment from an employee at Herzing University included an email from the university president, Renee Herzing, stating that, “If you have not already you need to make a comment/letter through this web site … E-mail me to confirm that you entered a comment -– we (are) counting our total comments.”

The lobbying efforts directed at members of Congress in recent months have been similarly strategic. During a “Hill Day” organized by the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities last month, the trade group handed out a series of tip sheets for students talking to the media, which were first obtained by CampusProgress, an advocacy group affiliated with the Center for American Progress.

Most of the instructions dealt with potential questions about student loan debt or recruiting tactics.

“Should a reporter ask if or how much debt you incurred at a career institution, you can firmly but politely reply: ‘I made an adult decision to invest in my education, and I am confident in my ability to meet my financial responsibilities,” one bullet point read. “Should the reporter continue to push on the debt point, you can politely but firmly reply: ‘I have answered that question, and am happy to talk more about how my degree/diploma/certificate has enhanced my career prospects.’”

(See the document here)

The Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities has represented the industry for decades. But last year, two of the larger publicly traded education companies, Education Management Corp. and ITT Educational Services Inc., joined other colleges to form a separate lobbying organization called the Coalition for Educational Success.

They brought on Davis, a former legal counsel to Bill Clinton, to lobby on their behalf last fall -- a time when scrutiny of the sector was reaching an all-time high.

The Department of Education had announced new rules, Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) had begun a series of hearings probing abuses in the industry, and the Government Accountability Office had released scathing findings from an undercover investigation of recruiting tactics at 15 for-profit schools.

The coalition and other corporations have brought on a wide array of lobbying expertise over the past year, employing many with deep connections to the committees and constituencies who could control the debate.

(Source: Analysis of data from the Center for Responsive Politics

Other major Democratic lobbying powers hired on for the fight include the Podesta Group, hired by Career Education Corp. and APSCU; and Steve Elmendorf, a major organizer for John Kerry’s 2004 presidential campaign, who was hired by the Washington Post Co.’s Kaplan Inc.

College corporations have also focused on outreach to minority lawmakers and interest groups, fueling the debate about access to education for disadvantaged groups.

One of the lobbyists hired from the Podesta Group is Paul Braithwaite, a former executive director of the Congressional Black Caucus, whose members have been split on the question of the gainful employment regulations. Former Maryland Congressman Albert Wynn Jr., a longtime member of the CBC, was hired by Bridgepoint Education Inc. of San Diego.

Other lobbyists had backgrounds with the National Association of Latino Elected Officials, on education committees in both the House and Senate, and as staffers with the Department of Education.

Corinthian Colleges Inc. brought on Gephardt, the former Democratic House leader for 14 years, and a number of his former staff members.

Aside from Davis, none of the lobbyists or firms mentioned in this article returned phone calls and emails seeking comment; but trade groups for the industry have defended the increased advocacy, arguing they are no different from other industries seeking to be part of the debate.

“I wouldn’t say that it’s unusual for companies that feel regulation is going to either put them out of business, or drastically change their business, to advocate for their point of view,” said Penny Lee, the managing director of the coalition.

Davis, who was lobbying for the Coalition for Educational Success until last week, said the outreach to Democrats has been a way to shift debate on the issue away from a traditional anti-government, pro-business perspective.

“I had an argument to make that was not a conservative, anti-regulation argument, and that was unusual,” Davis said. “I think they reached out to other liberal and Democratic lobbyists for exactly the same reason. It’s the ‘man bites dog’ point of view, because I’m criticizing my own fellow Democrats in the administration.”

GROWING REACH

The for-profit college industry’s influence has been noticeable during public hearings in Washington.

At a hearing last September focusing on recruitment practices at for-profit colleges, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) read aloud an op-ed letter written by Davis and published by The Huffington Post and other publications. The letter criticized Democratic support for the gainful employment rules.

“We’ve done a battle on many occasions,” McCain said, but later pointed out that, “I find myself in complete agreement with Lanny Davis.”

He then walked out of the hearing in protest, without noting the fact that Davis was being paid more than $40,000 to lobby on behalf of a number of schools.

Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.) noted that fact later in the hearing.

“Lanny Davis is being paid by the industry to make these arguments that we get regurgitated here,” Franken said. “I would appreciate it if the other members would stay, instead of making a comment, quoting a paid lobbyist -- with great umbrage -- and then leaving.”

For-profit education companies gave more than $18,000 to McCain in the last election cycle, making him one of the top recipients in the Senate.

McCain and other Republicans on the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee wrote a letter to committee chairman Harkin last week, asking him to reconsider holding a scheduled May hearing on for-profit colleges.

“Should you decide to decline this request, we will not participate in the next hearing on for-profit institutions,” the letter stated, calling the previous hearings “disorganized and prejudicial.”

The letter was released the same day the budget amendment was finalized, without the rider that would prevent regulations. Most of the Republicans who signed the letter have either not attended previous Senate hearings on for-profit colleges or have walked out in protest.

That letter and others sent by Republicans and Democrats fighting against regulations over the past few months have also focused on two lines of attack pushed by industry lobbyists: one against the Department of Education, and another against the Government Accountability Office.

Rather than focusing on the substance of the rules at issue, the industry has instead tended to assert that it is under attack by the federal government.

The coalition in particular has been vocal in criticizing the GAO, Congress’ independent investigative arm, over corrections made to an undercover investigation of for-profit college recruiting last year. The group has sued the GAO and publicly attacked the agency. Members of Congress have followed suit, calling into question the report’s findings.

The GAO has stuck by its conclusions in the report, which was updated to include tweaks to language and more elaborate descriptions after GAO lawyers reviewed undercover footage. Lobbyists for the industry say the changes should invalidate the entire report.

The video evidence shown, however, is compelling: Recruiters encouraged investigators posing as prospective students to falsify federal financial aid documents and refused to provide details about tuition costs until they had signed paperwork to enroll in classes.

“I don’t recall any kind of frontal assault the way they have mounted this one against the GAO,” said Barmak Nassirian, associate executive director of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars & Admissions Officers, which mostly represents nonprofit colleges. “We saw with our own eyes how they were lying to and defrauding students.”

The coalition has also sought to discredit the Department of Education by accusing department officials of conspiring to develop the regulations with Wall Street short sellers –- investors who profit when stocks tumble. The theory is based on four meetings that Department of Education officials had with short sellers who had done analysis on publicly traded for-profit schools, and a number of mostly one-way emails from four hedge fund managers to officials in the department.

Representatives of for-profit colleges, who are also invested in how stocks fare on the market, have met privately and publicly with top-level Department of Education officials and the Office of Management and Budget on nearly 50 occasions over the past year, according to public schedules posted by the department.

CRITICS GET CASH

Some of the most vocal regulatory critics in Congress have also been the most well-compensated by the industry.

Rep. John Kline (R-Minn.), who chairs the House Education and the Workforce Committee, received more than $40,000 in campaign contributions during the last election cycle. His political action committee, the Freedom & Security PAC, received an additional $35,000.

Kline was instrumental in introducing the legislation in the House that aimed to block the gainful employment rules, and led the effort earlier this month to have the prohibition included in the budget bill.

Rep. Howard “Buck” McKeon (R-Calif.), another longtime member of the education committee, received more than $20,000 from the industry in his personal campaign and more than $65,000 to his political action committee, the 21st Century PAC.

While McKeon was serving on the committee during the Bush administration, he owned stock in one company, Corinthian Colleges Inc., at the time the restrictions on online programs were being lifted.

Staffers for McKeon and Kline did not respond to requests seeking comment.

Democrats who have opposed regulations on for-profit colleges have also been rewarded with contributions. Reps. Andrews and Carolyn McCarthy (D-N.Y.), who signed onto the letter pushing for the budget bill rider, are among the top five recipients of campaign cash: Andrews received more than $70,000, and McCarthy more than $41,000, during the last election cycle.

Andrews said he has been involved with the industry for a long time and believes that career programs can offer many benefits for students.

“I do what I do based upon what I think is right,” he said. “I’m interested in the outcome for the student and the taxpayer, not on the outcome for the school. But I also disagree with people who say that by definition for-profit education is bad. I think bad education is bad, and I think we ought to come up with a measure to figure that out.”

One notable exception is Rep. George Miller (D-Calif.), the former chairman of the education committee until this year, who took in more than $105,000 from the industry -- the most of any single candidate in Congress.

His son also works for a lobbying firm in California that lobbies for Education Management Corp., the second-largest publicly traded college corporation.

But Miller has supported the Department of Education’s proposed regulations, and has been critical of attempts to delay or water them down.

A spokeswoman for Miller said the contributions are “completely separate” from any policy work. “The fact is that Rep. Miller has a long and successful track record of holding for-profit schools accountable and reforming this industry,” said the spokeswoman, Melissa Salmanowitz.

Other top recipients of campaign money who have not supported the industry include Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.), who took in more than $50,000; and Iowa Democrat Harkin, who received about $13,000 but has held a series of highly critical hearings probing the industry.

Looking at the February House vote, however, Democrats who supported the amendment to block regulations received on average nearly twice as much in political donations as Democrats who opposed the regulations.

Harris Miller, the president of the trade group representing for-profit colleges (who is not related to George Miller), downplayed the importance that political contributions play in changing policy, pointing to the donations to many who have actively opposed the industry.

“I know some people like to think there’s this simplistic correlation between writing a check and getting a vote,” he said. “I wish it were that easy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment