The Obama administration on Thursday issued a series of highly anticipated regulations aimed at cracking down on for-profit colleges and other career training programs that leave students saddled with unmanageable debts and contribute to an unequal share of federal student loan defaults.

The final rules issued by the Department of Education, however, are significantly less stringent than a draft version released last year, giving college programs an additional three years to come in line before possibly losing access to lucrative federal student aid dollars. The changes come after an unprecedented lobbying and campaign financeoffensive over the past year by the for-profit college industry, which derives a vast majority of revenues from federal student loan and grant programs and has sought to protect that income by gaining influence in Washington.

Education Secretary Arne Duncan said the changes came after discussion with "lots and lots of different folks," not just the industry, and he pointed out that the colleges were not unanimous in their suggestions for changes.

"What we really wanted to do was give people a chance to reform … this was not about 'gotcha,'" Duncan said. "We tried to be very thoughtful, very reasonable and give people every opportunity to succeed, but be very clear where we wouldn’t permit ongoing failure."

The rules have been in the making for nearly two years, amid evidence that students at for-profit institutions default on federal loans at a significantly higher rate and pay higher tuition than their counterparts at public universities, despite for-profit schools devoting significantly less money toward instruction.

The rules were derived as a way to bring accountability to the federal student aid system and to protect students from unscrupulous programs that sought only their federally subsidized tuition.

"The for-profit education sector business model invokes much of the same characteristics of what happened with subprime housing and securitization, namely that the schools can capture all of the upside of increased volume while shifting all of the downside risk somewhere else," said Gene Sperling, director of the National Economic Council. "In this case, that somewhere else is to students and taxpayers."

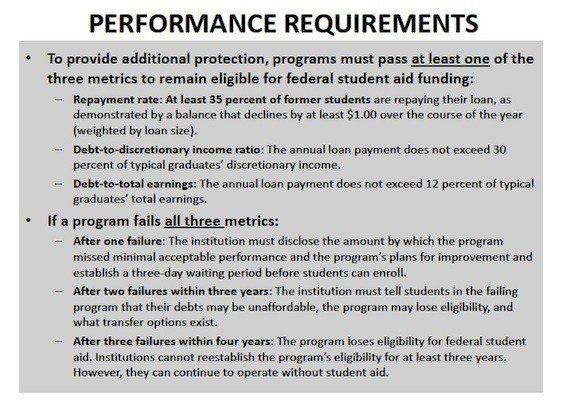

Specifically, the rules will measure student outcomes at such programs in two ways: whether students repay at least a portion of their student loans and whether a graduate has an excessive debt burden compared to his or her income.

Education Secretary Arne Duncan said the changes came after discussion with "lots and lots of different folks," not just the industry, and he pointed out that the colleges were not unanimous in their suggestions for changes.

"What we really wanted to do was give people a chance to reform … this was not about 'gotcha,'" Duncan said. "We tried to be very thoughtful, very reasonable and give people every opportunity to succeed, but be very clear where we wouldn’t permit ongoing failure."

The rules have been in the making for nearly two years, amid evidence that students at for-profit institutions default on federal loans at a significantly higher rate and pay higher tuition than their counterparts at public universities, despite for-profit schools devoting significantly less money toward instruction.

The rules were derived as a way to bring accountability to the federal student aid system and to protect students from unscrupulous programs that sought only their federally subsidized tuition.

"The for-profit education sector business model invokes much of the same characteristics of what happened with subprime housing and securitization, namely that the schools can capture all of the upside of increased volume while shifting all of the downside risk somewhere else," said Gene Sperling, director of the National Economic Council. "In this case, that somewhere else is to students and taxpayers."

Specifically, the rules will measure student outcomes at such programs in two ways: whether students repay at least a portion of their student loans and whether a graduate has an excessive debt burden compared to his or her income.

In order to be disqualified from the student loan program, more than 65 percent of students would have to be delinquent in repaying their loans, and graduates would need to have loan debts that comprise more than 30 percent of their discretionary income, or more than 12 percent of their total earnings.

A program would have to fail each of those three metrics in three out of four years in order to completely lose eligibility for federal student aid, as opposed to potentially losing eligibility after one year under the draft rules from last year.

That means programs cannot be disqualified from receiving federal student aid until 2015, as opposed to 2012 under the draft rules.

Groups that have criticized for-profit colleges expressed disappointment that the rules did not go far enough in protecting students from harmful programs, but said the reform will still address some of the worst abuses in the industry.

"I think it means that more bad programs that don’t serve students well will continue, but that many bad programs will be put out of business, or be forced to reform," said David Halperin, a senior vice president at the Center for American Progress who directs the group's Campus Progress arm. "It would have been better if the rule was stronger or kicked in sooner, but nevertheless I think over time, hundreds of thousands if not millions of students will be protected because this rule was issued."

Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), who has led a series of hearings probing abuses in the industry, called the regulations "a modest and important first step to protect students and taxpayers from subprime academic programs that have a demonstrated track record of failure."

Groups representing the for-profit college industry largely reserved judgment on the rule. Harris Miller, president and chief executive of the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities, said it appeared that the Department of Education listened to concerns they had raised.

But he said his group will bring on a third-party researcher to study the potential effects of the rule on students. Miller's group has sued the Department of Education over a series of other for-profit regulations relating to compensation of recruiters and misrepresentation of a program’s benefits.

"The bottom line is not whether the department makes changes or not, but what are the impacts of those changes to student access to higher education?" Miller said.

He did not say whether the group would file a lawsuit over this set of regulations.

Lanny Davis, a former special counsel to President Clinton who has lobbied against the regulations for for-profit colleges, noted that "there appears to have been some second thoughts" by the administration. Davis now lobbies for the National Black Chamber of Commerce, which has argued that the rules would restrict access to minority students who attend such institutions in greater numbers than in other sectors of higher education.

"We hope we can continue to see some changes in what is essentially a targeted regulation that has a disparate impact on low-income and vulnerable students," Davis said.

For-profit schools and their lobbying groups engaged in a vicious fight over the past year, accusing the Department of Education of coming up with the rules as part of a conspiracy with Wall Street short sellers, based on e-mails and a handful of meetings where Department officials viewed presentations. The Department of Education’s Inspector General disclosed at a hearing in March that she is investigating any potential improper communications, after Sens. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) and Richard Burr (R-N.C.) brought up the matter last fall.

The industry also publicly attacked the Government Accountability Office, Congress' investigative arm, over a series of corrections made to an undercover report that found widespread abuse and deception among recruiters at for-profit schools. The industry spent more than $8.1 million on lobbying in 2010, more than doubling spending of $3.3 million from the year before.

In addition to increased government regulation, the industry is facing a joint probe by attorneys general in at least 10 states, and the Justice Department has intervened in a lawsuit filed against Education Management Corp., a Pittsburgh corporation that owns numerous colleges across the country.

The original draft of the rules would have restricted growth at certain programs that failed loan repayment and debt burden measurements. The rules released Thursday require schools that fail to meet all standards to provide disclosures to students.

For example, although it takes three years of failure for a program to be ineligible for student loans, after one year of failure a school must tell students how the program failed to meet the regulation. And the school is required to give students a three-day waiting period before they are able to enroll.

After two years of failing to meet standards, a school must warn students that they may be unable to afford their debts and explain transfer options.

The regulations apply to individual degree programs, not entire schools. Although the rules are expected to have the most impact on for-profit colleges, there are more than three times as many public and non-profit vocational programs also subject to the new regulations.

Related:

Watch a Great PBS doc on For Profits

Even if you don't understand the article above once you see this document, you will!

No comments:

Post a Comment